When he's driving on

Mars, though, every rock he encounters is a new discovery, a step toward

humanity's knowledge of the planet he hopes to visit some day.

Maxwell has the dream job

of driving rovers on Mars, and he's gearing up to take control of the

biggest and most sophisticated one yet: Curiosity. He's one of about a

dozen people at NASA tasked with steering the $2.6 billion vehicle from

more than 100 million miles away.

"It's a priceless

national asset that happens to be sitting on the surface of another

planet," Maxwell says of the rover, which is set to land on Mars at 1:31

a.m. ET Monday. "You better take that damn seriously."

As a child, Scott Maxwell dreamed of visiting other planets; now he gets to drive rovers on Mars.

Maxwell loves to talk

about how much he loves his job, and his effervescence is infectious,

say colleagues at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, home to Curiosity's

mission control.

"The thing that always

impressed me about Scott was just the passion that he has for what we're

doing. He just loves being a rover driver," says Steve Squyers, a Mars

expert who's worked closely with Maxwell. "He thinks he's got the

coolest job on the planet, and he's right, I think."

The names of the rovers

Maxwell has driven so far -- Spirit and Opportunity -- speak to his

upbeat attitude and thirst for immersing himself in what he enjoys

doing.

Through his blog and Twitter account @marsroverdriver, Maxwell interacts with all sorts of self-professed "rover-huggers" -- people who really love rovers.

Earlier this week Maxwell tweeted, "VIP seats for opening night of @IndyShakes's Comedy of Errors! Last chance to see a play before the baby comes Sunday."

The baby, of course, is

the SUV-sized Curiosity, coming to Mars after years of planning and

preparation. It's been more than eight months since it left Earth, and

no one can be sure exactly how it will behave, says Maxwell.

Over dinner in Old

Pasadena this week, Maxwell and his girlfriend, Kim Lichtenberg -- a

planetary scientist also working on the rover mission -- playfully

compared it to having a child, though neither has had children.

"We're all going to be kind of like new parents," Lichtenberg says.

"Watch it take its first steps," Maxwell adds.

Landing Curiosity will be such an amazing feat of engineering that NASA is billing the process "seven minutes of terror."

Like anxious parents,

scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena are eager to see

the rover arrive safely, and so are the reporters who have flooded the

NASA campus.

Maxwell says he has

confidence in the JPL team responsible for the entry, descent and

landing of the spacecraft. But if the amazing maneuver goes wrong, the

whole effort will have been "all for nothing" for the many people who've

sacrificing family time and vacations to pour their hearts into it.

"That seven minutes tells you whether the last seven years of your life had a point," Maxwell says.

A voyage to break down the wall

Maxwell's eyes widen

with joy when he talks about the parts of life he thinks are "awesome":

His girlfriend. His other NASA team members. The Independent Shakespeare

Company (@IndyShakes). His first lemon drop cocktail. The Cotswolds.

Something about

Maxwell's thin frame, boyish features and the way he gets giddy over

esoteric things resembles Jim Parsons' character on "The Big Bang

Theory," although Maxwell is more jovial and socially gracious than

Sheldon Cooper. His arms seem almost impossibly long as they move about

while he explains the rover driving process.

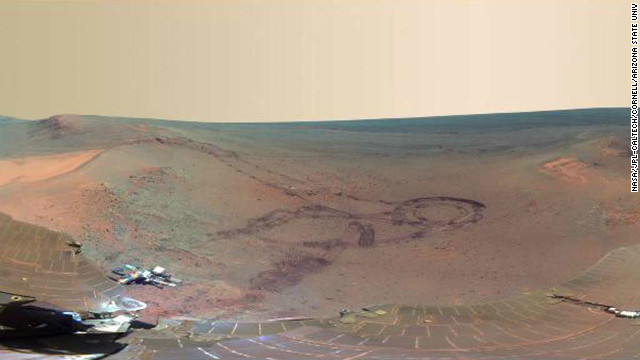

NASA reveals panoramic view of Mars

NASA reveals panoramic view of Mars

With a youthful

complexion and hair that finishes in a short tail on the back of his

neck, it's impossible to guess Maxwell is 41. The first time he ever had

lunch with Lichtenberg, she thought, "Aw man, he's way too young for

me. Way too young for me." Later she found out she's about six years his

junior.

Lichtenberg, fair and blond, grew up with the space program close at hand: Her father is astronaut Byron Lichtenberg,

a NASA payload specialist who's flown on two shuttle missions. She has a

Ph.D. in planetary spectroscopy, which deals with the interaction of

matter and radiation in planetary environments.

Maxwell, on the other hand, had long assumed that a career in space was out of reach.

He was raised in an

economically depressed rural area of eastern North Carolina, although

his accent could just as well place him from the Midwest. His parents

divorced when he was 7; after his mother moved to Florida, he spent time

bouncing between the two states until college.

His father was a railroad engineer for most of his career, although he previously worked as a dean at various colleges.

Carl Sagan was Maxwell's

childhood hero. He adored watching the 13-part TV series Sagan hosted

called "Cosmos: A Personal Voyage," first broadcast in 1980 on PBS.

In one episode, the

scientist talked about what it would be like to go to Mars. Only last

year, Maxwell watched the episode again and remembered it mentioned a

prototype Mars rover, which at that time seemed a futuristic idea.

"I realized in that

moment that that's where I get this sense that I've grown up and stepped

into this fantasy world that I had when I was a kid, because I have," he says with excited emphasis.

As a child, Maxwell

loved imagining what it would be like to go to other planets. But as an

older teen, he assumed he would study hard and end up in a career that

seemed more common and attainable than space exploration, such as

banking.

"This kind of thing

always seemed to me like the kind of thing other people do," he said.

"There's me. And there's this big invisible glass wall. And there are

people who are doing stuff like that."

Maxwell believed he could never cross over to the other side of glass wall.

Mission Control for Curiosity at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

It wasn't until he got

hired by NASA, after completing his master's degree in computer science,

that he realized the wall never existed.

Maxwell is living his

fantasy now, but he hasn't always had such luck. At age 20, while

double-majoring in English and computer science at East Carolina

University, he learned that his swollen lymph nodes were a symptom of

stage 2 Hodgkin's lymphoma. The cancer had spread in his neck and chest.

He went through nine weeks of radiation treatments and has been

cancer-free ever since.

Just days after the

treatments ended, he left for graduate school at the University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Going from a state school to a prestigious

engineering institution, he was floored on the first day when a

professor expected everyone to have already learned the material in the

first six chapters of an algorithms textbook. Maxwell had to quickly

catch up on his own but says he loved learning so much at once.

And though he feared he

couldn't afford his master's degree, he found work with the research and

development arm of the U.S. Army and left school debt-free.

He had intended to go to Illinois to work toward a Ph.D., but ultimately the cancer changed his priorities.

"I was interested in going out and making tools for people to use," he says.

JPL came to recruit at

his school in fall 1993, and he remembers telling the recruiter how he

was fascinated by NASA's Voyager mission -- twin spacecraft that had

photographed Jupiter in unprecedented detail. His excitement apparently

made an impression: He landed an interview at JPL in January 1994, and

started his job that June.

Today, he lives on a

quiet Pasadena street, in a cozy house that boasts some of his nerdy

treasures, including an extensive collection of science fiction books.

"But then my life became science fiction," he said, explaining why he's

reading more Shakespeare and Dickens these days. As he shows off his

collection, his cat Molly purrs, demanding his attention. The brown and

black marbling on her otherwise white fur looks somewhat like the

Martian landscape, although that's not why he adopted her.

A glass-paneled cabinet

hosts metallic "Star Wars" and Mars rover lunch boxes. There's a vial of

a substance he calls KimSim, a material his girlfriend helped create to

figure out how to rescue the Spirit rover after it got stuck in a "sand

trap" of alien soil on Mars in 2009.

And there are stones

from the Cotswolds, an area in England he bubbles with excitement over.

He says, "Wait, wait," like a child about to demonstrate a new toy, and

runs to get a book filled with images of the region. He likes the views

from the ground better than the aerial shots -- ground-level is more

like what a rover would see, he explains.

The wider,

well-manicured street perpendicular to his own, with larger houses and

roses growing on front lawns, is the sort of place where he'd always

wanted to live, but he says the houses are "wicked, ridiculous, crazy

expensive." Still, he loves the house he bought, with the added bonus of

a lemon tree growing at its side.

It's a bit like how he loves his job driving a vehicle on Mars, even though he dreamed of becoming an astronaut.

"Things in my life aren't quite how I pictured them," he said, "but they rhyme."

At NASA, not just a sojourner

It's been 18 years, but

Maxwell still occasionally interrupts himself to say things like "I

can't get over that I work at a place called the Spacecraft Assembly

Facility" when he mentions that building at JPL.

James Wang, test conductor for Curiosity, with the test model of the rover used for experiments on Earth.

For the first couple of

months there, Maxwell felt like he was in a foreign country where he

didn't speak the language. He says it was fun to be clueless about the

acronyms his colleagues were throwing around. "Now, I'll use 10 acronyms

in a sentence and won't think twice about it," he says, "but you kind

of have to pick up the culture."

He started out working

on software to decode data from spacecraft. He also wrote software to

help coordinate various teams working around the world to get commands

to spacecraft.

In the mid-1990s,

Maxwell was asked if he wanted to work on a mission called Mars

Pathfinder. Maxwell had no idea what that was, and working on the team

didn't appeal to him.

What he didn't know was

that Mars Pathfinder would mark the first time NASA had sent an

untethered robotic device to another planet. The 90-day mission was

carried out by a rover named Sojourner.

"I just thought that was

super cool, that really just captured my imagination, that you could go

for a walk on another planet," he says. "Not with your squishy, frail,

human body, but you could design a robot body that would go to Mars for

you."

Although he passed up

that opportunity, another chance came in 1999 when Brian Cooper, who'd

driven Sojourner, approached Maxwell about developing rover-driving

software for the next Mars mission.

"More or less before the

words were out of his mouth -- like, 'Do you want to come work on this

project?' -- I was like, "YES! Yes! I'd like to come work on this

project, that'd be the coolest thing in the world, yes!"

That mission was

eventually scrapped, but their efforts were put toward a different

endeavor that did take off: Spirit and Opportunity, the twin Mars

exploration rovers that launched in the summer of 2003.

Maxwell helped write the

software that rover drivers would use for the pair, as well as for

Curiosity. He would soon move from writing software to using it to

command -- and ultimately drive -- the rovers.

His first time

commanding a rover was on his 33rd birthday, in 2004. Spirit hadn't

started moving across the Mars surface yet, but Maxwell and his

colleague were checking out the instruments. Maxwell told the rover to

ignore the state of a switch on one of the instruments -- not exactly

driving, he said, "but by golly, I commanded a Mars rover that day."

The real drama came

about three weeks later when he got behind the wheel, so to speak. He

remembers obsessing over what he had to do, checking everything multiple

times, before sending the driving instructions.

He remembers going home

afterwards: "I'm lying there, looking at the ceiling, realizing there's a

robot on another planet doing what I told it to. And that notion of,

'I'm getting to do this. I'm not dreaming about this anymore. It's real

for me now.'

"I reach out across 100

million miles of emptiness and move something on the surface of another

planet. That feeling has never left me."

The opportunity to drive

You might think a rover

driver would control the vehicle using a joystick and virtual reality

interface, much like a video game. That's not how it works. The reason

for that: Signals take at least four minutes to travel from Earth to

Mars (it could take up to 20 minutes, depending on where the planets are

in their orbits), and then the same amount of time for confirmation

data to come back.

So rover drivers don't

tell the vehicle to move forward and then wait several minutes for

confirmation that it happened before sending the next command. Instead,

drivers spend their days writing directions for what the rover will do

the next day, sometimes even a few days if it's a holiday weekend.

Maxwell and colleagues

spend the Martian night generating a single batch of commands, which

they send to the rover after the vehicle sees sunrise. Drivers work in

overlapping 8- to 10-hour shifts preparing the rover for the day ahead.

"It's as if we're e-mailing the rover its to-do list for the entire

day," Maxwell explains. And at the end of its day, the rover sends

information back saying what it did. During the Martian night, the rover

goes to sleep.

That might sound risky,

letting a vehicle roam around on a planet for several hours without

someone guiding its every move in real time. But safety checks are built

in. Curiosity will know how far its wheels are moving up and down, so

it will stop if it heads into something deeper or higher than the

drivers had planned. In that sense, the rover is more like a boat than a

plane -- stopping is a fine course of action if additional direction is

needed, Maxwell explains.

Curiosity can travel up

to about 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) per minute, says rover driver John

Wright, but in practice it will go a lot slower because the science team

will want it to stop and examine its surroundings. A rover may stop and

take photos, or -- as will be the case with Curiosity -- the scientists

will want it to stop to perform chemical analyses.

Scott Maxwell wears 3-D glasses to simulate driving a Mars rover at JPL's Mission Operations area.

Photos the rover takes

of its surroundings help the drivers determine where to send it next.

The drivers use a 3-D simulation created from the photos to visualize

what the rover is seeing. The virtual model of Mars lets drivers work

out which commands to transmit each day. Video games have helped several

rover drivers hone their skills, including Maxwell, since driving on

Mars requires planning and multidimensional thinking.

Any game that shows a

large open world, such as "World of Warcraft," can hone these skills,

says Cooper, the first rover driver and the only person to have driven

all three rovers NASA has landed on Mars.

"You're essentially

driving a robot with a keyboard 100 million miles away," says Maxwell.

"You can't always believe what the simulator tells you. If anything does

go wrong, there's no one there to hit the panic switch."

Besides being manually

controlled, the rover also has the capability to drive by itself,

detecting hazards through cameras and driving around them. This

autonomous mode takes more time, however, so it's employed less often.

Curiosity is landing in

Gale Crater, where it may find evidence the area once was a lake. It

will take at least a year to drive Curiosity to its ultimate

destination, Mount Sharp, where the rover will examine layers of

sediment for organic molecules, which would be signs -- but still not

proof -- that life may have existed on the planet.

Maxwell will see some of

the images Curiosity takes before anyone else does, but he loves that

the public will get to view them soon after on NASA's website. "I get to

take everybody in the world along in the backseat," he said.

Beyond rover driving,

Maxwell genuinely loves the science of Mars. The rover science team has

its own busy agenda, but during the mission involving Spirit and

Opportunity, Maxwell would point out rocks that might be interesting to

examine further, or suggest photographing the sunset on a given day.

Sometimes the science team would take him up on his ideas.

"He's always looking to

try to get as much out of the vehicles as possible," says Squyers, lead

scientist of the Mars Exploration Rover mission, which involved Spirit

and Opportunity. "Scott is, within the bounds of safety, one of the most

enthusiastic rover drivers there is."

The spirit of his first car

There's a special love

that Maxwell has for Spirit, the first rover he ever drove. Spirit was

only supposed to last about 90 days, but the rover kept operating for

more than five years.

When Spirit got stuck in

May 2009, Maxwell felt like he was in an Indiana Jones movie, trying to

rescue the vehicle. The rover's wheels broke through a crust and the

vehicle fell into a sandy trap called Troy, like a car driving into a

pool of flour. Even before the accident, one of its six wheels had quit

working.

Scott Maxwell, top, Kim Lichtenberg, left, and Pauline Hwang test how to get Spirit out of a Martian "sand trap."

Maxwell and his

colleagues were almost able to pull Spirit out, but not quite. They had

figured out a technique, but with the Martian winter coming, the solar

panels were tilted away from the sun. Plus a second wheel malfunctioned

during escape tactics. Over the winter, something broke -- Maxwell says

humanity may never know what.

The Opportunity rover,

which Maxwell has also had a hand in driving, is still operating. Still,

he is nostalgic about the Spirit.

"It's very much the way

you feel about your first car," Maxwell says. "Spirit was my first car.

She was just on Mars. That was the emotional closeness that I felt to

her."

Even after it stopped

moving, Spirit was able to continue scientific operations until March

2010, when NASA lost communication with it. The place it got stuck

turned out to be extremely interesting -- while trying to escape, the

rover found soil rich in minerals called sulfates, a component of steam,

suggesting that there may have once been conditions on Mars able to

support life.

It -- or rather "she," says Maxwell -- accomplished this with an attitude of "persistence and determination and never say die."

Scientists kept trying to communicate until May 2011, when they gave up.

"Spirit will be there

for a million years, but I sure hope that there are Martian cities

surrounding her," Maxwell says. He envisions trails commemorating the

rovers' paths and hopes people someday will be "walking the Spirit

trail."

Loving to be curious

Given the busy schedule and odd hours, it helps to be in love with someone who works on Mars, too.

Maxwell and Lichtenberg

had been hearing each other as disembodied voices on NASA conference

calls for years, while Lichtenberg was a graduate student at the

University of Washington in St. Louis. She visited JPL with her adviser

on the five-year anniversary of the Spirit and Opportunity mission.

They met in person at a

group lunch; each thought the other was attractive. Maxwell spent a

couple days working up the nerve to ask her out and finally did on the

day beloved science fiction author Ray Bradbury gave a surprise speech

at NASA. Maxwell began by asking her, "Is anybody doing anything

tonight?" She said a group was going out; he replied that he wanted to

go out with a cute girl he'd just met. After she realized he meant her,

she said yes -- much to Maxwell's astonishment.

This week, just days

before the Curiosity landing, the couple had dinner with me at a quaint

Mediterranean restaurant in Pasadena's Old Town. When they weren't

holding hands, Maxwell was putting his arm around the back of her chair.

As they said goodnight for the evening, they kissed three times -- and

both said they planned to stay up late and sleep in to practice shifting

to Mars time.

Part of the fun of

working on Curiosity will be living on Mars time for about the first 90

days, Maxwell says. The days on Mars are 40 minutes longer than on

Earth. That means Maxwell might start at 8 a.m. Monday, 8:40 a.m.

Tuesday, 9:20 a.m. Wednesday and so on. Before long, he'll be working

overnights.

"I like to say I sleep 40 minutes more, I actually work 40 minutes [more]," he said.

Lichtenberg is the

co-lead on the science planning team for the Curiosity mission. That

means she helps other scientists decide what they will do with the rover

every day, given how much power and time the tasks will take and how

much data will be required.

On their first date

about three and half years ago, Lichtenberg was sold when Maxwell told

her that while healing from a martial arts-induced shoulder injury, he

decided he would read all of Shakespeare's plays. And he did.

"He really sticks to his

convictions, and I really, really like that about him," Lichtenberg

says. "Being around him makes me want to be a better person."

Maxwell insists that

Lichtenberg did not move to Southern California for him. She agrees that

she wanted to work at JPL anyway, but Maxwell was at least "a small

bit" of the decision. These days they work down the hall from each

other, and although they are on the same operations team, they are

assigned to different shifts.

Scott Maxwell and Kim Lichtenberg have been dating for more than three years; both work on Mars rover missions.

The affectionate, happy partners share a love of Mars and, if possible, would both like to go some day.

"If NASA set up a flight tomorrow, I'd be the first one. They wouldn't have to bring me back," Maxwell says.

He'd be gone in a snap,

even if there were just one seat. Lichtenberg, although she likes the

idea of visiting Mars, is not sure she'd just pack up and go by herself.

"I totally understand that you would," she tells him. "It's OK, I accept that. Totally."

"It's not that I like Mars better than I like you," he assures her. They peck each other on the lips.

But there is something

powerful that draws Maxwell to Mars. It's partly the idea of being on

the surface of another world. There's also his own mortality. He

believes the radiation treatments he had in his 20s will ultimately lead

to a different form of cancer (he actually had a possible thyroid

cancer a few years ago, which turned out to be benign). Maxwell

estimates -- without a hint of regret in his voice -- that he has about

20 years left to live.

"I've only got so long

anyway, you might as well make it something really good. Right? You

might as well make it count," he tells me and Lichtenberg. "And what am I

going to do that's going to be better than actually going to Mars? Go

on, name three things I'm going to do that are better than that."

"Drive a Mars rover," says Lichtenberg.

Maxwell agrees his job is "awesome" but says going to Mars would be "even better."

With that level of passion and spirit, Maxwell may one day indeed follow his Curiosity.

Retweet this story

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete